(by Pam Hunt)

2025 was the second year that NH Audubon participated in the range-wide effort to track Wood Thrushes using the Motus Wildlife Tracking Network. The project as a whole, coordinated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, tagged 1250 birds over two years: 1109 in the U.S. and Canada and 141 in Central America during the winter of 2024-25. In 2025, we attached lightweight nanotags to another 34 thrushes, bringing our two-year total to 61. This total turns out to be the fifth-highest single-state total out of 26 states – and the ones ahead of us are much larger. The exceptional NH effort wouldn’t have been possible without help from our partners at Antioch University, the Harris Center for Conservation Education, and the Tin Mountain Conservation Center. Birds from both batches are currently on their way south, and while data for the 2025 fall migration are still coming in there are enough available to tell a few stories.

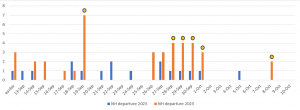

For starters, 32 of the birds tagged in 2025 are alive and well and on their way south, along with 10 of the 11 that returned from 2024. Departure dates ranged from late July to October 8, with half of them September 19-29. This departure schedule is roughly five days later than 2024, and large peaks of movement occurred on nights with good conditions for migration: generally strong west or north winds (Figure 1). These same winds helped thrushes move all the way into the mid-Atlantic region (e.g., Pennsylvania, Maryland) on the same days they left NH, and average first detection in that area was only two days later than NH departure. This contrasts with 2024, when average NH departure and mid-Atlantic arrival dates were five days apart, and there were fewer clear peaks. The reason? The fall of 2024 was marked by unusual easterly winds, and very few nights with optimal migration conditions. As a result, the 2024 thrushes spread themselves out over the entire departure range in late September. This year’s fall migrants arrived in the southeastern U.S. (SC, GA, FL) mostly during the first half of October, and by the end of the month, five had already crossed the Gulf of Mexico and been detected by a Motus station in Honduras. Of the five birds that were detected in Central America in the fall of 2024, three didn’t show up until after mid-October, so there is still plenty of time for more of the 2025 migrants to appear south of the border.

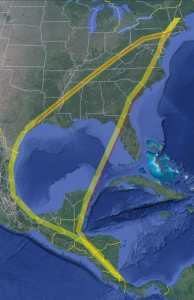

Because the tags we used last over a year, we’ve been able to track two consecutive fall migrations for 10 birds, plus one spring migration. Most spring migrants were not detected until they reached the mid-Atlantic region at the very end of April, and they were back in NH a few days later. Why weren’t they picked up in the southeast like they were in the preceding fall? One possibility is that their spring migration was shifted farther west, as shown by a thrush from southwestern NH. This bird, tagged in Hinsdale, made it all the way to Costa Rica by November 2024. It next appeared over the Texas coast in May 2025, suggesting it went around the Gulf to some extent, and may have continued its northward migration to the west of the Appalachians (Figure 2). Unfortunately, this bird does not seem to have returned to NH (although it was over Connecticut on May 22), and we don’t have any southbound detections for 2025.

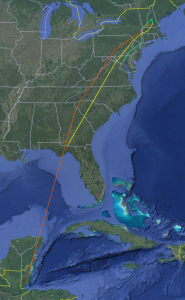

Back to those birds with three seasons of data. Figure 3 shows tracks for bird #597, one of three tagged at NH Audubon’s McLane Center in the summer of 2024. He flew south along the Appalachians (typical of most birds that fall) and eventually crossed the eastern Gulf of Mexico to the Yucatan. Where he spent the winter is anyone’s guess, but it was probably farther east in Nicaragua or Costa Rica. Like most other spring returns, he went undetected until he was almost back and probably spent the summer in the same territory he held in 2024. His next southbound flight follows the same general route south, a pattern typical of the other nine birds for which we have two falls of data. Overall, however, their paths seem shifted slightly to the southeast, and I wonder if this is because we didn’t have prevailing easterly winds in September and October of 2025.

In areas such as the mid-Atlantic region and South Carolina/Georgia, where there are lots of Motus stations, an individual thrush may pass over several stations in succession over the course of a single night’s flight. In such cases, we can calculate a rough estimate of flight speed and a minimal estimate of migration distance. A sampling of the available data shows Wood Thrushes travelling between 40 and 60 mph, with some of the differences likely related to wind conditions. Two of the longest flights this fall were over 400 miles, in both cases from central NH to the Chesapeake Bay area. Both birds flew for at least 7.5 hours with an average speed of 57-60 mph. What’s harder to tease apart is how long birds rest between flights, since most of the time they land where there’s no station to detect them. The gap between arrivals in the mid-Atlantic and Southeast suggests stopover might average a week, but it will take more detailed analysis of the data to figure out that particular aspect of Wood Thrush migration ecology.

And with over 1000 thrushes being tracked between the two years of this project, that is exactly what project partners across North America hope to learn, among many other things. Having a better idea of migration timing and duration, stopover location and duration, and overall routes used in different parts of the range will allow biologists to better develop conservation strategies to help this declining species recover. We’ll be keeping you informed as the 2025 birds return next spring and undertake their second fall migration, and when all the data are in and analyzed, we’ll be able to share the big picture view of Wood Thrush migration across the species’ entire distribution: from Minnesota to Maine to Costa Rica.