(by Pam Hunt)

Fall migration is here, and while many birders focus on the warblers, thrushes, and sparrows starting to wing their way south, there’s another popular migrant species that’s probably familiar to a lot more people – often from the comfort of their living rooms. Arguably, the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) is among the most well-known birds in eastern North America, right up there with chickadees, cardinals, Bald Eagles, and Canada Geese, and it is without doubt the smallest.

For such a small bird, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds have a lot of attitude, and are known to chase all manner of birds much larger than they are – including raptors! But most of their ire is directed toward other hummers – or perhaps the occasional pollinating butterfly or bee – and late summer is the perfect time to observe these little aerialists in all their pugnacious glory. Young have usually fledged by late July, resulting in a noticeable increase in numbers at feeders and gardens. When more than one hummingbird has located a good nectar source there’s likely to be a turf war of some kind, as more dominant individuals repeatedly chase others away from “their” feeder. You might think there’s plenty of nectar to go around, but hummingbirds didn’t evolve in a world where flowers had a seemingly-infinite supply like feeders do. As a result, they’re doing what they’d do in “natural” conditions and defend a reliable source of food like their lives depend on it.

Which may very well be the case. Hummingbirds have extremely high metabolic rates and need to feed almost constantly to fuel their active flying lifestyles. If a human scaled their diet to that of a hummingbird they’d need to consume over 150,000 calories a day – that’s roughly 600 average energy bars. A day. Don’t try this at home. At night, when they can’t forage, hummingbirds often go into torpor: lowering their body temperature so less heat is lost to the cooler evening air. Hummingbird physiology can be even more impressive during migration, when these tiny birds (they weigh the same as a penny) build up fat reserves – sometimes almost doubling their weight – to fuel sustained flight. This is enough for them to fly over the Gulf of Mexico, although most probably take the long route around to reach their Central American wintering areas.

And speaking of migration, contrary to popular belief, keeping feeders out does not prevent hummingbirds from leaving in the fall. Our birds are mostly gone by the end of September (with males leaving before females and immatures), and unless there’s something wrong with them they’re not going to stick around. Later in fall, however, is when vagrant hummingbird species from the West sometimes occur in New England, and these are usually discovered at feeders. That said, these other species are exceedingly rare, and females and immatures in particular can be very hard to separate from Ruby-throats. The species most likely to be confused with the Ruby-throat is Black-chinned, which has never been recorded in New Hampshire. If you see a male hummer with a dark throat, it’s just an effect of lighting and not a mega-rarity from the Rocky Mountains.

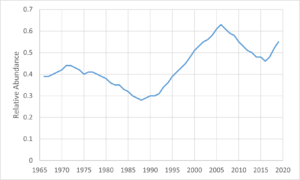

Unlike many recent “birds of the month,” Ruby-throats are doing well in New Hampshire, as shown by the graph below. Although there have been ups and downs (which I have no logical explanation for), the general trend is increasing, and overall the species is maybe 50% more common now than it was in the 1970s. This success is at least in part due to its adaptability, seeing as how it’s just as much at home in a suburban yard as it is in a forest clearing. As long as there are nectar-rich flowers available there will probably be hummingbirds to feed from them. Of course, as befits a common backyard species, hummers are susceptible to all manner of suburban threats, be they chemicals, windows, or outdoor cats, and will benefit if these dangers are reduced or eliminated.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Developed, forests, shrublands

- Migration: Medium distance

- Population trend: Increasing

- Threats: Cats, collisions

- Conservation actions: Provide native plants for food and nesting, avoid pesticides, keep cats indoors

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available at: https://www.nhaudubon.org/conservation/the-state-of-the-birds/