(by Pam Hunt)

Our state bird (Haemorhous purpureus) was featured on the cover of the first State of the Birds report in 2011 and thus deserves its moment in the monthly spotlight. Like October’s Winter Wren, it breeds throughout New Hampshire but is far more common in the north and west in coniferous and mixed forests. In contrast to the wren, it can be quite conspicuous: singing from treetops in spring and summer and flocking at feeders in fall and winter – sometimes.

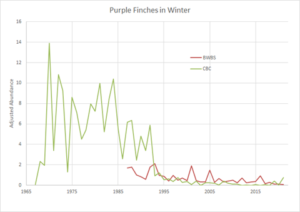

Like many finches, the Purple Finch is an “irruptive” species, meaning that the numbers we see in the winter fluctuate widely depending on food supply to the north. During the winter, they feed on a variety of seeds including conifers and mountain ash (plus sunflower at feeders!). If there is a good seed crop in their core range in Canada, fewer will migrate south in the fall, and we’ll see lower numbers at feeders. But when food is scarce to the north they’ll migrate south until they find some, and numbers can be higher. Here in New Hampshire, peak fall migration generally occurs in October and November, and birds move back north in April. You can see these ups and downs in the data in Figure 1, but what’s the story behind the sudden decline in the 1990s?

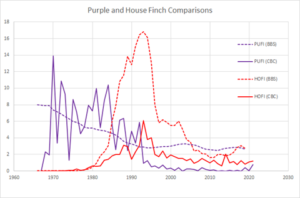

There has been much speculation on why Purple Finches are declining, but the species is not well-studied despite being widespread and fairly common. As a northern species, it could be responding to climate change – or to related changes in habitat or food supply – but we simply lack the data needed to evaluate this hypothesis. Another option, proposed in the 1980s, is that Purple Finches were negatively influenced by competition with the closely related House Finch. The latter is not actually native to eastern North America. It was accidentally introduced to New York City in 1939, gradually spread north, west, and south, and eventually merged with the original range in the western United States. House Finches didn’t arrive in New Hampshire until the 1970s, and weren’t common until the mid-1980s, but as shown in Figure 2 their increase occurred at roughly the same time as Purple Finches started to decline. The interaction between the two species has only been studied once, but this study found that House Finches were dominant over their native cousins 90% of the time. Could reduced access to food during winter carry over to lower reproductive success as has been shown for other birds? More study is clearly needed.

There’s a more recent twist to this story: the sharp decline in House Finches that occurred in the mid-1990s (Figure 2). This was caused by a major outbreak of conjunctivitis that was first detected in the mid-Atlantic region in 1994 and subsequently spread rapidly through the Northeast. Mortality was high in the initial years of the outbreak, and House Finches have remained much less common (but no longer declining) since the early 2000s. Purple Finches seem to have stabilized around the same time, lending further credence to the competition hypothesis. Note also that New Hampshire’s breeding Purple Finches (dashed line in Figure 2) have not declined as strongly as those that winter here. Time will tell if the decline of our state bird has relented, and whether new threats such as climate change may have future impacts, but for now enjoy them if they grace your feeders this winter. Be sure to distinguish them from House Finches though, since the latter remain far more common in New Hampshire except in Coos County and at higher elevations. You’re also encouraged to collect data for NH Audubon’s annual Backyard Winter Bird Survey to help (see link below) us track these population changes.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Spruce/Fir and Hardwood/Mixed forests

- Migration: Short-distance

- Population trend: declining, but less so recently

- Threats: poorly understood, but could include forest loss, climate change, and competition with House Finches

- Conservation actions: Keep cats indoors, clean and take in feeders if you see signs of disease

NH Audubon’s Backyard Winter Bird Survey will occur on February 12-13, 2022.

More information on The State of New Hampshire’s Birds.