(by Pam Hunt)

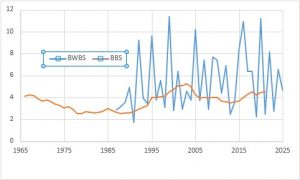

While goldfinches are found in New Hampshire all year, the ones we see in winter might not be the same ones that nest here. It is a little-known fact that goldfinches, like most other finches in the Northeast, show a strong biennial cycle of winter abundance (Figure 1). This is obvious in Backyard Winter Bird Survey data and reflects a varying number of birds moving south from Canada (where they are relatively rare in winter). Presumably, these irruptions are driven by food supplies, as they are for goldfinch relatives like Redpolls and Pine Siskins, but the species has not been extensively studied in the northern portion of its range. What about the goldfinches that breed here? Those populations have also fluctuated over the years (Figure 1), but not as dramatically, and the contrast between summer and winter trends indicates that there is something more complicated going on. Perhaps some of our nesting goldfinches leave in the winter and are replaced by their Canadian cousins, or perhaps they stay put, and visitors from the north supplement the local birds.

Another interesting facet of goldfinch biology is the extreme lateness of their nesting season. They feed their young primarily small seeds (e.g., thistle and other plants in the daisy family) and thus need to wait until late summer when these become more abundant. Nesting in New England typically doesn’t begin until July, meaning that there will still be goldfinches with young in nests as late as September. Their reliance on seeds to feed their nestlings provides goldfinches with an unexpected benefit when it comes to parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbirds. Apparently, this diet is missing nutrients that cowbird chicks need, and few survive longer than three days.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Forests, Shrublands, Developed Areas

- Migration: Short Distance

- Population trend: Stable

- Threats: Predation, Collisions

- Conservation actions: Maintain a bird-friendly yard

You can help collect valuable data on American Goldfinches and other winter birds by participating in NH Audubon’s “Backyard Winter Bird Survey.” The survey will occur on February 14-15, 2026. Visit here for details.

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available here. Full species profiles in the format of “Bird of the Month” are now available here.