(by Pam Hunt)

As we start the winter feeder season and lead up to NH Audubon’s Backyard Winter Bird Survey (see below), I thought it’d be fun to have something of a theme for upcoming “Bird of the Month” articles in the eNews. That theme is “Feeder Finches,” and we’ll start off with the familiar House Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus), which turns out to have quite an interesting backstory.

All the House Finches we see in New Hampshire are the descendants of a handful released on Long Island in 1939. Originally native to Mexico and the southwestern United States, they were brought east to be sold as pets until – so the story goes – they were freed by a pet store to avoid persecution under migratory bird protection laws. It took a while for the finches to get a toehold in the New York City area, but by the 1960s they had spread to southern New England and Chesapeake Bay. The first New Hampshire records came in 1967 with birds in Hillsborough and Concord, and since then the species has spread through most of southern New Hampshire, although primarily where there are people.

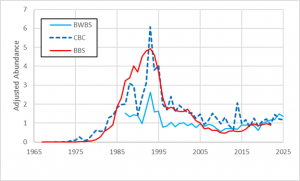

The rapid rise of House Finch populations in the East was curtailed in 1994 by the emergence of a conjunctivitis strain that caused considerable mortality, and numbers dropped quicky to the much lower levels where they remain today (Figure 1). The birds’ high vulnerability to this disease was likely due to low genetic diversity since all House Finches east of the Great Plains descended from those original birds released on Long Island. Numbers remained low for most of two decades but now appear to be increasing slowly, a sign that perhaps the species has evolved some resistance to the disease Conjunctivitis is still present in New Hampshire finches, so if you see birds at feeders that are lethargic and have crusty or swollen eyes you should take in the feeders, clean them thoroughly, and wait two weeks before putting them back outside. This will minimize the risk of transmitting the disease to other birds.

For a non-native bird, the impact of House Finches on native species appears minimal. The exception might be the Purple Finch, which showed declines during the 1970s and 1980s as the House Finch was increasing. After the latter’s precipitous decline in the 1990s, Purple Finch populations stabilized over much of the Northeast. The only study of interactions between the two species showed that House Finches were socially dominant over Purples at feeders, which certainly could have had negative effects on winter survival. And while their population is no longer in steep decline, Purple Finches are still outnumbered by House Finches in southern New Hampshire, even during invasion years. Telling the two apart is a common problem for backyard birders. The best field marks to look for are the shade of red (Purples have more of a raspberry tinge than plain red), streaking on the underparts (male Purples have none), and facial pattern (female Purples have a distinct whitish triangle around their cheeks).

Which feeder finch will be featured next? Look for the January eNews to find out.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Forests, developed areas

- Migration: Resident

- Population trend: Stable

- Threats: Predation, collisions, disease

- Conservation actions: Maintain a bird-friendly yard

You can help collect valuable data on House Finches and other winter birds by participating in NH Audubon’s “Backyard Winter Bird Survey.” The survey will occur on February 14-15, 2026. Visit here for details.

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available here. Full species profiles in the format of “Bird of the Month” are now available here.