(by Pam Hunt)

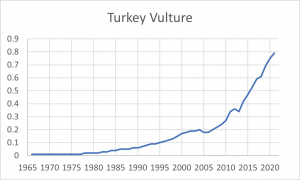

Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura) are a relatively recent addition to New Hampshire’s avifauna, having expanded their range northward starting in the mid-1900s. They didn’t become regular in southern New Hampshire until the 1960s and weren’t recorded nesting until 1979. It’s likely they bred earlier however, since nests can be extremely hard to find. Vultures usually lay two eggs in a cave, jumble of boulders, large hollow log, or even dilapidated building, and generally in inaccessible places. If you happen to stumble upon a nest you’re likely to be greeted by an unnerving hiss from the chicks, a noise that sometimes sounds like a rattlesnake rattle. If you get too close, there’s a reasonable chance the young birds will regurgitate in your direction.

This diet of carrion has proven to be a boon — and more recently, a bane — for Turkey Vulture populations. Biologists speculate that their northward expansion was facilitated by the expansion of roads — and thus roadkill — in the United States during the 20th century. They are certainly most frequently spotted soaring over interstates and other open developed areas. But while they are occasionally killed by vehicles, the threat is not in where they eat but in the food itself. Starting in 2021, a new strain of avian influenza virus made its way into North America from Europe and started killing waterfowl and domestic chickens. “Bird flu,” as this disease became colloquially known, made the news and has even been detected in people and livestock in recent years. It turns out that even the digestive juices of vultures were no match for this strain of virus, and they were infected after consuming by the carcasses of other wild birds that had already died. Since arriving in North America, bird flu has killed hundreds (if not thousands) of vultures and other birds of prey, although so far there don’t seem to be any notiable impacts on the overall population.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Hardwood-mixed Forests, Rocky and Alpine, Developed Areas

- Migration: Variable

- Population trend: Strongly increasing

- Threats: Disease

- Conservation actions: None identified

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available here. Full species profiles in the format of “Bird of the Month” are now available here.