(by Pam Hunt)

Back in May, volunteer Brenda McMahon was checking nest boxes at the Massabesic Audubon Center and took this photo of a Black-capped Chickadee nest. If you look closely you’ll see a larger egg in the lower center of the clutch – indicating that this chickadee nest was “parasitized” by a Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater). Unlike all manner of invertebrates that act as parasites by living on or in a host organism, cowbirds are what ornithologists call “brood parasites.” Such birds lay their eggs in the nests of other birds, leaving these hosts to incubate them and care for the young, and thus take no parental responsibility whatsoever. For this reason cowbirds are frequently vilified by bird lovers, although from the cowbird’s perspective they seem to have managed a very good deal. There are five species of parasitic cowbirds in the Americas, and the Brown-headed is by far the least selective. Their eggs have been recorded in the nests of well over 100 species, including those – like ducks – that are totally unsuitable for the intended purpose. It is believed that a single female cowbird can lay as many as 40 eggs in a season. Chickadees, and cavity nesters in general, are rarely selected as hosts, which makes Brenda’s discovery all the more interesting.

Female cowbirds need to be this prolific because not every egg is going to be successful. Some species (finches, the aforementioned ducks) are simply poor hosts; eggs laid in their nests will either never hatch or die as very young chicks. Several other species are wise to the cowbird’s ruse and will either remove eggs other than their own (e.g., catbirds), abandon their nest and start over, or build a new nest on top of the cowbird eggs and try again. Yellow Warblers are famous for the latter strategy and have been recorded adding up to five new nests atop the original, each with a cowbird egg buried underneath. If the eggs are accepted, the host will usually fail to rear any of their own young. For one thing cowbirds hold their eggs in their oviducts longer than normal, so that when laid they have a head start on incubation. When a young cowbird hatches it may push smaller host young out of the nest, or if not, it will grow faster and monopolize the food brought in by its foster parents – leaving the host chicks to starve.

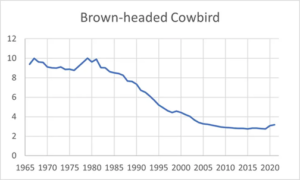

Cowbirds were historically a bird of the Great Plains, where they followed herds of bison. Their parasitic behavior served them well in this situation since they didn’t spend much time in any one place. As European settlers cleared forests and started farms, cowbirds spread east into newly opened areas and began to parasitize species that had no previous experience with this behavior. Some rare and endangered species, like the Kirtland’s Warbler of Michigan, suffered greatly from reduced reproductive output to the extent that local cowbird control efforts had to be implemented. Ironically, cowbird populations themselves have declined over most of their range, including New Hampshire (Figure 1), perhaps because of factors as varied as reforestation in the Northeast or changes to agricultural practices in the Midwest and Great Plains.

So instead of berating cowbirds for their poor parenting skills and taking advantage of other birds, think of how well adapted they are to their way of life. The species they parasitize here in New Hampshire don’t seem to be significantly threatened by parasitism, and given recent declines it’s unlikely they’ll be a danger in the future. If you find a cowbird egg in another species’ nest, just let nature take its course (and besides, cowbirds are protected along with other migratory birds).

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Developed Areas, Grasslands

- Migration: Short-distance

- Population trend: Decreasing

- Threats: Blackbird control in winter grounds

- Conservation actions: More data are needed on population trends and magnitudes of threats

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available here. Full species profiles in the format of “Bird of the Month” are now available here.