(by Pam Hunt)

The Cedar Waxwing (Bombycilla cedrorum) is the most frugivorous bird that occurs in New Hampshire. Most of their lives, including migration and breeding, are timed to take advantage of seasonal availability of fruit, and they only consume significant numbers of insects in spring and summer when fruit is relatively scarce. During the non-breeding season, waxwings gather in large flocks (often a hundred or more) and wander widely in search of concentrations of food. Prior to European introduction of ornamental fruiting plants, key dietary items included species that retain fruit well into the winter, such as red cedar and mountain-ash. Now the flocks are just as likely in crabapples, honeysuckles, and autumn olive. Since they consume only the fleshy pulp of these berries and pass the seeds, waxwings are highly effective seed dispersers for native and non-native plants alike.

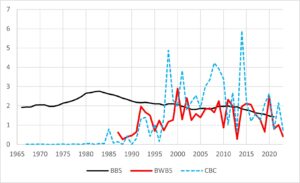

But fruit crops vary in space and time, and for most of the year waxwings are nomadic. When a flock discovers a food source they will settle down until the fruit is consumed, and then move on. As a result their occurrence is unpredictable most of the year, as shown by the winter data (BWBS and CBC) in Figure 1. Look closely at this figure and you’ll see that in some years the peaks occur in the same winter (e.g., early 1990s, 2020) while in others they do not. This is probably because the two counts are conducted at different times: the CBC in late December and the BWBS in mid-February. The intervening weeks provide plenty of time for waxwings to arrive or depart from a given area as they travel around the Northeast in search of fruit. In contrast, breeding populations (BBS) show little fluctuation. While local populations have been relatively stable over the last 50 years, there have often been strong increases to our south. These are again suspected to be related to fruit, particularly the increased planting of ornamental trees and shrubs. Such plantings are also probably behind the increase in wintering waxwings starting in the 1990s.

No matter where they were over the winter, waxwings return to most of New Hampshire in mid-to-late May in preparation for breeding. This is the time of year when insects are most important since few plants are producing fruit. Even then, however, fruit drives much of their behavior. For instance, waxwings are not strongly territorial like other songbirds, presumably because large concentrations of berries are not easily defended. They even delay nesting until July and August so that fruit is more abundant to feed their young. And because young birds are fed primarily fruit, waxwings are a poor-host for the parasitic Brown-headed Cowbird. Most cowbird eggs are rejected outright by waxwings, but if they survive to hatching the fruit-heavy diet is insufficient for cowbird growth and there are no records of waxwings raising cowbird chicks to fledging.

No discussion of waxwings would be complete without a nod to the waxy tips on their wing feathers for which they are named. Although the true function of these structures is not known, their size and number increase with a bird’s age, and they may thus serve a purpose in mate selection. Another interesting note on waxwing plumage is related to the yellow tip to their tail feathers. In parts of the Northeast you may find birds with an orange tip, a result of red pigments in non-native honeysuckle berries that are incorporated into the feathers if consumed in large enough quantities.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Forest edges, developed areas

- Migration: Short-distance

- Population trend: Stable

- Threats: Cats, collisions

- Conservation actions: Maintain a wildlife friendly yard (minimize window strikes, keep cats indoors, plant native plants).

NH Audubon’s “Backyard Winter Bird Survey” will occur on February 10-11, 2024. Visit here for details.

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available here.