(Story and photos by Pam Hunt)

For a bird lighter than a robin, the Northern Shrike (Lanius borealis) is an aggressive and tenacious predator. During the breeding season in the far north, they feed primarily on insects but supplement this diet with small birds and mammals. When they move south for the winter the proportions flip, and birds and rodents predominate. This is especially true in places like New Hampshire where insects are absent entirely in the colder months. Shrikes are ambush hunters and are most often seen perched high on a tree or power line surveying a patch of open habitat. Prey are captured in the feet and – in the case of vertebrates – dispatched with a bite to the neck that severs the spinal cord. For this purpose they have a small “tooth” on their upper bill much that those of falcons.

Shrikes lack the raptorial talons of hawks and owls, which makes it harder to hold prey down while it is being eaten. Instead they carry it to something that will secure it for them, such as a thorn, fork in a branch, or barbed wire. Only then can they start methodically tearing apart their meal with the bill. From this behavior shrikes have earned their nickname of “butcher birds,” with the thorn or fork serving the hook upon which human butchers used to hang their meat. Despite their size, Northern Shrikes have been recorded killing and carrying away birds as large as a pigeon (five times the shrike’s weight). Smaller fare are more typical, but birds slightly larger than the shrike are still common prey, including robins, Blue Jays, and Mourning Doves. Mammals eaten are almost entirely mice and voles.

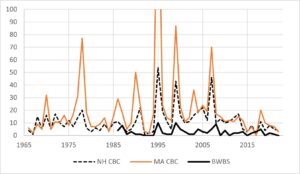

Although regular winter visitors, Northern Shrikes are not easy to see in New Hampshire. Their numbers vary significantly among years (Figure 1), and they occur at low densities. Some years, however, see larger than typical incursions from the north, much as are seen with classic irruptive species like winter finches. Figure 1 shows that these irruptions are synchronous within a region and even using different survey methods. The reasons for these fluctuations are poorly known but are presumed to include variation in boreal mammal populations (e.g., lemmings).

Because the Northern Shrike nests so far north, there are no data on population trends during the breeding season. For some species winter data can fill this hole, but shrikes are rare and variable enough that doing so is difficult. The best we can usually do is look at extremely large scales, and this sort of analysis suggests declines in western North America and slight increases in the east. It’s probably not even possible to detect a trend for New Hampshire, so just enjoy shrikes when you see them, even if they’re hunting chickadees at your bird feeders this winter.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Shrubland, breeds in open areas of boreal forest and shrubby areas of tundra

- Migration: Short-distance

- Population trend: Uncertain

- Threats: Poorly known, may include habitat loss

- Conservation actions: None identified