(by Pam Hunt)

The Scarlet Tanager (Piranga olivacea) is one of the most eagerly awaited migrants to return to New Hampshire each spring. The stunning red-and-black males can be difficult to see high in the forest canopy, but it’s a lot easier in mid-May before the leaves are fully out. In many parts of their range, their “preferred” leaves are those of oaks, and Scarlet Tanagers are one of the characteristic species of oak/pine forests across much of the central United States. Toward the northern edge of their range where oaks become rare, including in much of NH, they occupy northern hardwoods such as sugar maple, beech, and birch, sometimes with a few hemlocks thrown in. Tanagers tend to forage high in the canopy on caterpillars and other large insects, and during the nesting season are more often heard than seen. Their song is often described as resembling “a robin with a cold,” and is uttered by both males and females, sometimes with the female following the male’s song immediately with her own. Also distinctive is their “chip-burr” call – another indication that there is a red or green bird above you in the canopy where you can’t see it!

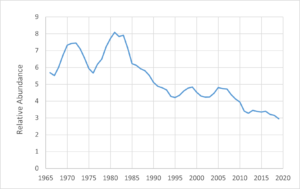

Like the Winter Wren (Bird of the Month for October 2021), Scarlet Tanagers can be susceptible to inclement weather. This usually creates problems during unusually cold and/or wet periods after spring arrival in mid-May, sometimes leading to birds visiting feeders because insects are less active. If adverse conditions persist, there can be significant mortality. Such an event occurred in late May of 1974, when observers reported dead or moribund tanagers along roadsides across central New Hampshire. Enough birds died that the population dropped noticeably and remained low for several years as seen in Figure 1. Although numbers rebounded just as quickly, the 1980s saw the beginning of a longer and more sustained decline that continues to the present.

The decline is believed to be due largely to habitat loss. Scarlet Tanagers are a bird of the deep forest and often disappear from the smaller woodlots that are left behind when land is converted to homes, businesses, and farmland. Some estimates place the minimum forest size needed for tanagers at 40 acres, and this number can be larger in landscapes that are more developed. In smaller forest patches, tanagers are believed to be more susceptible to both nest predation and nest parasitism (by Brown-headed Cowbirds), and thus produce fewer young in a breeding season. Even in larger forest blocks, suburban sprawl continues to eat away at the edges. And like many of our other declining forest birds, Scarlet Tanagers spend the winter at mid-elevations in the Andes of South America, an area at increasing risk from habitat loss due to expanding agriculture and human populations.

Male Scarlet Tanagers are only red for half the year. After breeding they gradually replace all their body feathers with an olive green (hence the “olivacea” in the scientific name). They keep their black wings and tail however, which allows them to be distinguished from similarly-plumaged females – whose wings and tails are grayish-brown. In late winter, while still in South America, the males molt again to replace the green with scarlet and are again ready to wow observers in the north after our long dreary winters.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Hardwood and mixed forests

- Migration: Long-distance

- Population trend: Strongly declining

- Threats: Habitat loss and fragmentation (including on winter grounds), cats, collisions

- Conservation actions: Protect large unfragmented forest blocks, minimize new fragmentation, keep cats indoors

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available at: https://www.nhaudubon.org/conservation/the-state-of-the-birds/