(by Pam Hunt)

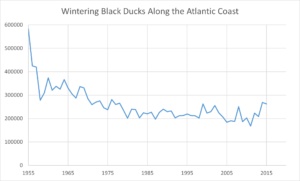

October and November comprise the core of fall waterfowl migration, when a lucky observer may encounter dozens if not hundreds of ducks and geese in a local wetland. Among them may be the only duck considered a “species of greatest conservation need” in New Hampshire: the American Black Duck (Anas rubripes). Once the most common duck on the east coast, black duck populations had declined by roughly half by the 1970s, leading wildlife managers to implement stricter hunting regulations in 1983. Since then, the species has started to stabilize, as shown in the graph below.

As for the Mallard, this species was historically absent from much of the black duck’s range, but moved east from the Great Plains in the wake of increasing agriculture and urbanization. This sometimes put it in conflict with black ducks, which are less tolerant of altered habitats. At the same time, the species’ co-occurrence led to increased hybridization, although the jury is out on the extent to which this negatively affected black ducks. Either way, Mallards are here to stay, meaning that black ducks will remain relegated to areas with lower human disturbance for the foreseeable future.

In part because they are hunted, American Black Ducks are the focus of constant conservation attention, and most of this currently revolves around habitat. The Atlantic Coast Joint Venture (https://acjv.org/) identified it as one of its three focal species and is working to protect or enhance enough coastal habitat to support a million wintering ducks (roughly three times the current population). In New Hampshire, most wintering black ducks occur on Great Bay, where efforts to improve water quality will help the full diversity of water birds that use this estuary.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

-

Habitat: Freshwater wetlands, salt marsh

-

Migration: Short-distance

-

Population trend: declining, with some recent stabilization

-

Threats: wetland loss, hybridization with Mallards, human disturbance

-

Conservation actions: wetland protection, reduce pollution, continued hunting limits

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available on our website.

Photo: American Black Ducks on the Merrimack River, along with a pair of Mallards (left), by Pam Hunt.