(by Pam Hunt)

Given the numbers of turkeys one encounters throughout NH in the 21st century, it’s hard to believe there were none here for over 100 years. The Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) is one of only two species of turkey in the world, the other being the Ocellated Turkey of the Yucatan Peninsula. Wild Turkeys originally occurred throughout eastern and southwestern North America, and south into much of Mexico. The Mexican birds are in fact the ancestors of the domestic turkey, the only domesticated animal from the Western Hemisphere that has spread widely to other parts of the world. Turkeys appear to have been first domesticated about 2000 years ago, and independently in two widely-separated areas: southern Mexico and what is now the southwestern United States. Turkey bones found at Mayan ruins even suggest that there was trade in the species away from where it was domesticated. In that same vein, all the domestic turkeys we see today are probably descended from birds taken back to Europe by the Spanish in the 1500s.

Some of those descendants were probably brought back to New England in the early colonial period, where settlers also encountered the native wild variety. There is no record of which – if either – was served at the first Thanksgiving. Either way, the native turkeys’ time was limited, and through a combination of hunting and habitat loss it was extirpated from New Hampshire by the 1850s. For the next 120 years there were no turkeys in here at all.

In 1969, NH Fish and Game began releasing turkeys in the southern part of the state, starting around Pawtuckaway State Park. This early restoration attempt got off to a slow start due to harsh winters, but a second series of releases in the Connecticut Valley beginning in 1975 seems to have stuck. Writing in the species account in NH’s Breeding Bird Atlas (1994), State turkey biologist Ted Walski noted that the species was established in lowlands south of the Lakes Region. He also posited that “their range is unlikely to expand north of Lake Winnipesaukee” due to habitat and winter limitation.

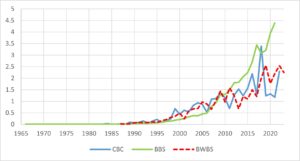

Sometimes biologists get our predictions wrong, and anyone reading this from north of Winnipesaukee will have already made that same observation. The Breeding Bird Atlas occurred in the early 1980s, when turkeys were still pretty rare in the state – they don’t even register on Figure 1 until five years later. But then, starting in the 1990s, the population took off, and they have now been found in every town in the state. Clearly turkeys found the habitat and climate north of the Lakes Region suitable, and it’s also possible that both those things have improved for turkeys over the last few decades.

It was reasonable to assume that habitat and climate might limit the turkey’s expansion throughout NH. One of their primary foods is mast (especially acorns and beech nuts), and masting trees aren’t found statewide. In addition, heavy snow can cover nuts and other seeds on the ground, making it more difficult for turkeys to forage. But turkeys are clearly an adaptable species, and their expansion north has likely been aided by a moderating climate and alternative foods such as corn. Harsh winters can still take a toll on populations in Coos County, and turkeys remain absent from higher elevations.

So, as you prepare to possibly eat a turkey this Thanksgiving, take a moment to reflect on the dramatic journeys the species has made – from domestication in central Mexico two millennia ago to Europe and back to New England, and from local extirpation to one of the more prevalent species on the present NH landscape.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Hardwood-mixed Forests, Shrublands, Grasslands

- Migration: Resident

- Population trend: Strongly increasing

- Threats: No major threats

- Conservation actions: Some habitat management is still required to ensure an adequate mix of habitats, and hunting is still used to manage population numbers.