(by Pam Hunt)

Most people probably don’t pay a lot of attention to Common Grackles (Quiscalus quiscula). Although they’re colorful enough in the right light, they don’t have a particularly attractive song and often come across as a noisy and aggressive “background” bird when you’re looking for something else. But what do we really know about them?

For one thing, they are one of the most abundant birds in North America, with a population estimated at almost 70 million. Along with other blackbirds, they are well-known for forming large communal roosts during the non-breeding season. Here in New Hampshire these roosts are largest in October and November, when they may host over 100,000 birds (although 3000 is a more typical high count). Roosts can form in a variety of habitats, including forests, swamps, and other wetlands, and the best time to observe the birds is at dusk or dawn when they are arriving or leaving. Seeing one of these “rivers of blackbirds” is a special treat both in early spring and late fall. Roosts are even larger in the winter in the southeastern U.S., where they can contain over a million birds. (Watch a video of just such an event in Portsmouth, NH.)

The Common Grackle’s gregariousness has not made it popular with agricultural interests, since large flocks of blackbirds can cause extensive damage to crops. In addition, roosts in urban areas are messy, noisy, and potentially a source of disease. As a result, grackles are viewed as pests in some areas and subject to a variety of control measures, including hazing, spraying crops to make them distasteful, or – in some cases – killing the birds themselves.

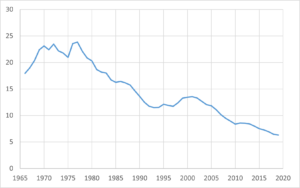

And this leads to another thing about grackles that most people don’t know: they’ve declined by about 50% across most of eastern North America over the last half-century. This decline has been significant enough for the species to be listed as a “common bird in steep decline” by Partners in Flight and as “near threatened” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Is blackbird control one of the causes of this decline? It’s suspected, but biologists honestly don’t know, and there is also concern about threats like habitat loss and even climate change.

It’s never easy to reconcile our own economic interests with bird conservation, and the conflict between blackbirds and agriculture is a case in point (watch for a “Bird of the Month” focused on grassland birds in 2023!). Since the species is still extremely abundant, is it justifiable to curtail control efforts and risk higher crop losses? Or should we strive for solutions that balance both interests and allow grackles some breathing room while acknowledging that they’ll not likely return to their pre-decline numbers? At the same time, those higher numbers might even have resulted from post-European agricultural expansion, in which case we’re caught in something of a chick-and-egg situation. Either way, coming up with workable solutions to such issues is ultimately both an art and a science.

It’s also possible that declines are driven in part by threats on the breeding grounds. There is increasing evidence that pesticides and pollution can have significant effects on aquatic insect populations, and such insects comprise an important part of grackle diets during the breeding season. Could compromised food supplies contribute to the declines in some way? Other species that share grackles’ habitat, including Eastern Kingbirds and Yellow Warblers, are also showing poorly-understood declines, so there’s always more to the puzzle than meets the eye. And always more to learn about some of our most common birds!

- Habitat: Shrublands, Wetlands, Developed

- Migration: Short-distance

- Population trend: Strongly declining

- Threats: Blackbird control, pesticides, pollution

- Conservation actions: Minimize use of insecticides, prevent mortality from cats and windows