(by Pam Hunt)

Sometime in late April the first Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) will return to New Hampshire from their tropical wintering grounds, potentially as far away as the pampas of Argentina. This species is a common and familiar sight over most of the state, building their mud nests on buildings and bridges and foraging over nearby open areas. Given their propensity for man-made structures, it’s reasonable to wonder what they did before European colonization of North America. Records of nests built on Native American dwellings in the early 1800s indicate a long history of association with people, but in the absence of such structures the vast majority of Barn Swallows nested in caves. This behavior is now rare, and the species is almost entirely reliant on humans for nesting sites.

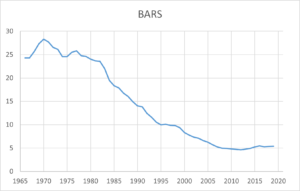

While they certainly increased following their association with people, the tide has turned for the Barn Swallow, and like many other aerial insectivores its populations are in steep decline (Figure 1). The decline is evident across most of North America, with the increases primarily in the southern tier of states. Overall, there are estimated to be 25% fewer Barn Swallows in North America than there were in the 1960. Reasons for the decline are poorly understood, although there has been a lot of speculation on the role of intensified agriculture. Increased use of pesticides, along with loss of edge habitats as fields expand, could easily result in significant changes in swallows’ insect prey. There is increasing evidence of widespread declines in insect populations, and researchers are actively investigating the potential role of food supply in swallow population trends.

Insects can also be suppressed by unseasonable weather such as spring cold snaps or extended periods of rain, and weather is expected to become more volatile as climate change effects accumulate. When flying insects aren’t active, aerial insectivores have more trouble finding food, and nests will fail when swallows can’t provision their young. The good news for the Barn Swallow is that the decline seems to have slowed in the early 2000s. This same pattern was noted in Canada, where the species was moved from “threatened” to “special concern” in 2021. Whether this means that the still-unknown threats have abated – or the species is adapting to them – remains to be determined, but there is hope that this adaptable bird will continue to for decades and centuries to come.

Just how adaptable is the Barn Swallow? In addition to its widespread use of built structures, it is one of a handful of birds – and the only songbird – to occur on all continents save Antarctica (but it’s been recorded on the South Shetland Islands 100 miles north of the Antarctic Peninsula!). It breeds across the temperate zone of the northern hemisphere, including parts of northern Africa, and winters on the southern continents. In the 1980s it was discovered breeding in Argentina, where the local population has been slowly increasing since. These birds are presumably derived from wintering birds that failed to return north in the spring, and rapidly adapted to a breeding season six months offset from all other Barn Swallows on the planet. And just like “our” swallows, they depart the nesting area as winter approaches, with recent studies suggesting they migrate north to northeastern South America during the austral winter (our summer). For all we know they encounter “our” Barn Swallows as the latter head south each fall.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Grasslands (farms), Developed

- Migration: Long-distance

- Population trend: Strongly declining

- Threats: Declines in prey populations, climate change,

- Conservation actions: Avoid use of pesticides, don’t remove nests from buildings

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available at: https://www.nhaudubon.org/conservation/the-state-of-the-birds/