(Photos and story by Pam Hunt)

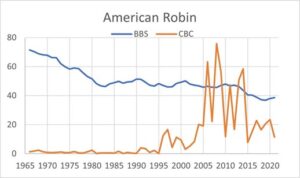

The American Robin (Turdus migratorius) is one of the most familiar birds in North America. Unlike other contenders like cardinals, bluebirds, and chickadees, it occurs across the continent from arctic Alaska to the mountains of southern Mexico. Populations north of southern Canada are migratory, and shift into the United States as winter progresses, while some in western mountainous areas move downslope into the deserts of the southwest. Here in New Hampshire, while robins have traditionally been considered a sign of spring, their abundance as an overwintering bird began to increase in the 2000s (Figure 1). They are now found year-round except in much of Coos County and the White Mountains, but spring is still heralded by arrivals from farther south and the onset of more frequent singing.

This subtle range shift is testament to the robin’s adaptability. While historically a species of forests and forest edges, robins quickly took to human-altered habitats. They are one of only a handful of birds that readily nest directly on buildings (e.g., gutters and porch lights) and even nest on the ground in some areas. Robin nests are easy to recognize by the layer of mud between the outer layer of grass and the lining of finer materials, and if in a well-sheltered space they will persist in good condition through the winter. Sometimes nests will be re-used for subsequent broods within a season. With a warming climate, robins in New Hampshire are breeding earlier and earlier, and in some parts of the state three broods are increasingly common.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Developed, Forests, Shrublands, Grasslands (for foraging)

- Migration: Short-distance

- Population trend: Stable

- Threats: Predation, collisions, additional unknown threats

- Conservation actions: Maintain a bird-friendly yard

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available here. Full species profiles in the format of “Bird of the Month” are now available here.