(Photo and story by Pam Hunt)

Nuthatches are famous for their habit of climbing down trees headfirst, a feat aided by their unusually long hind claws. But they just as often climb sideways or upwards in their search for insects and their larvae hidden in the bark. As people with bird feeders know, they also consume large numbers of seeds, and regularly take extra food away to cache in tree crevices for later use. If a seed has a strong shell in need of opening, the nuthatch will hold it against a hard surface and hammer at it with its bill, and this behavior is the source of the group’s common name.

Most research on this nuthatch has been done in the winter, when they join mixed flocks with chickadees and titmice. In flocks the nuthatches stick to the edges and aren’t typically as noticeable as the other species. Also, because they’re territorial they drop in and out as the flock travels through the woods. For this same reason you’ll almost never see more than two White-breasted Nuthatches at your bird feeders. The benefit of joining flocks for nuthatches is believed to relate to predation risk, since chickadees and titmice are more vigilant and regularly alert other birds to danger with unique calls.

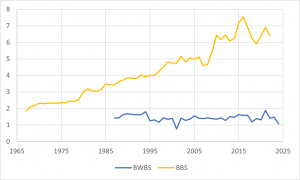

Like many species that don’t migrate, White-breasted Nuthatches are increasing, as shown in the BBS trend in Figure 1. No one’s really looked at reasons for this trend, but it’s similar to those seen for other non-migratory feeder birds like Downy Woodpecker and Tufted Titmouse (but not Black-backed Woodpecker – a story for another time), so factors such as increased forest cover and adaptation to developed landscapes may play a role.

But if nuthatches are increasing, why doesn’t this show up on the winter trend (BWBS)? I’ve already answered this question above: it has to do with winter territoriality. In other words, no matter how many nuthatches are out there, a person is only going to see one or two in their yards, and thus the stable trend for the BWBS. Data from the Christmas Bird Count (not shown), which are collected over much larger areas, also show the population roughly doubling over the same period as in Figure 1. Having more nuthatches scattered across the landscape doesn’t translate to there being more in your yard.

Enjoy their antics nonetheless!

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Developed areas and forests (less common in spruce-fir)

- Migration: Resident

- Population trend: Strongly increasing

- Threats: Predation, Collisions

- Conservation actions: Maintain a bird-friendly yard

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available here. Full species profiles in the format of “Bird of the Month” are now available here.

You can help collect valuable data on White-breasted Nuthatches and other winter birds by participating in NH Audubon’s “Backyard Winter Bird Survey.” The survey will occur on February 8-9, 2025. Visit the Backyard Winter Bird Survey webpage for details.