(Story and photos by Pam Hunt)

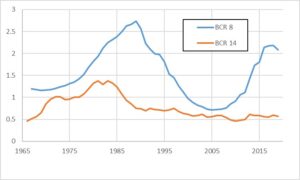

Despite its name (it was first “discovered” by Europeans in New Jersey), the Cape May Warbler (Setophaga tigrine) is a classic bird of Canada’s boreal forest, barely entering the US to breed along the border. Here in New Hampshire it was relatively common in Coos County during the Breeding Bird Atlas in the early 1980s, but had become scarce by the 1990s and has largely remained hard to find during the breeding season. This decline led to it being considered a species of conservation concern in the early 2000s, but as Figure 1 shows, sometimes we need to look at population trends over even longer periods to fully understand what some birds are doing.

Yes, there were steep declines through the early 2000s, but if we look father back these were preceded by an increase during the 1970s that was almost as steep. And now, at least to our north, Cape Mays are on the increase again. Such extreme fluctuations over a decadal time span are unusual for most of the birds highlighted in “Bird of the Month,” so what’s going on here?

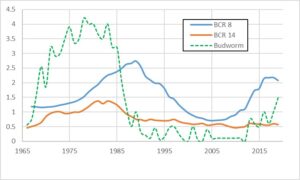

The answer, in a word, is caterpillars. Cape May Warbler is one of a handful of birds considered specialists on Spruce Budworm (the others are Bay-breasted and Tennessee Warblers and Evening Grosbeak), a moth whose caterpillars prefer the foliage of fir and spruce and which is known for population cycles lasting 30-40 years. When budworm is common, the “budworm birds” tend to produce more young than usual (the Cape May’s clutch size averages larger than other warblers), and when it is rare these specialists might be absent entirely from large portions of their ranges.

The last big budworm outbreak lasted from 1967 to 1993 and is estimated to have affected 136 million acres. Because it poses a threat to the forest products industry, budworm is carefully tracked by states and provinces, which measure defoliation from the air and set up traps to capture the adult moths. Figure 2 shows the moth trapping data from Maine added to the warbler data, and you can see the latter tracking the former, albeit with a bit of a lag. Also in Figure 2, you can see the recent uptick in budworm activity starting around 2013, which is spillover from a new outbreak in Quebec that started around 2006 and is still going strong. So far it has affected at least 25 million acres.

And while we haven’t seen an increase in breeding Cape Mays in NH during this new outbreak, we are seeing them in migration. Numbers reported to eBird have been going up for over a decade as more birds are produced in the boreal forest to our north. Some years are better than others, and so far 2023 is shaping up to be a banner fall. Both Cape May and Bay-breasted Warblers appeared in central NH relatively early, and there were even double-digit counts of Cape May by mid-August. The 2023 surge could also be due to the wildfires raging in eastern Canada this summer, which likely impacted nesting success and could have driven birds south early.

All the Cape Mays were seeing this fall are heading to the Caribbean, where most of the population winters. Here their diet changes dramatically, and while they still eat insects they also consume significant amounts of nectar and fruit juices. They obtain these with a somewhat tubular tongue that is unique among warblers. Because of this foraging shift, they can be frequent visitors to gardens and other disturbed habitats with abundant flowers and fruit, and in general are one of the more common wintering warblers of the islands.

What the future holds for Cape May Warbler depends in part on happenings in the boreal forests to the north. If the ongoing budworm outbreak continues to expand, the warbler will continue its upward trajectory. Attempts to suppress the outbreak could have the opposite effect, or at least result in bird populations leveling off. Wildfire remains a bit of an unknown, especially since such large fires are historically rare in eastern Canada. Extensive forest loss will obviously reduce available habitat, and if there was low productivity in 2023 the warbler populations in subsequent years could be lowered as well. We might not really know for sure until the current budworm runs its course.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Spruce-Fir Forest

- Migration: Long-distance

- Population trend: Declining, but see above

- Threats: Habitat alteration (pest control, invasive pests, climate change)

- Conservation actions: Manage spruce-fir forests to allow natural insect cycles to continue.