(by Pam Hunt)

If there is a New Hampshire bird species that more people have heard than seen it is the whip-poor-will, and its distinctive call can elicit a variety of responses. For some, if the bird is literally on their doorstep or near an open window, the response is akin to “Will it ever shut up?!” But far more people lament the fact that they hear it less frequently or not at all, and the question “Where are all the whip-poor-wills?” is not an uncommon one posed to NH Audubon staff. And when these same people actually do hear one, they excitedly let us know.

This variation in the human experience nicely sums up the history of the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferus) in the Granite State. Although we lack standardized data prior to the mid-1900s, early reports indicate that it was widespread south of the White Mountains. This was still generally true when NH completed its Breeding Bird Atlas in the mid-1980s, although by that time people had started to notice declines across the northeastern United States. When several states repeated their Breeding Bird Atlases in the early 2000’s, they discovered a roughly 50% decline in the area where whip-poor-wills occurred, and concern for the species increased.

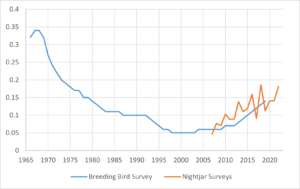

Over this same time frame, whip-poor-will populations were also declining on the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), a nationwide system of roadside monitoring routes established in 1966 (Figure 1). But the BBS is conducted during the day, and an observer has a remote chance of hearing a whip-poor-will at only the first couple of survey points, and as a result the trends obtained from the BBS were not terribly robust. The need for a better monitoring plan led NH Audubon and our partners to develop a specialized monitoring protocol in the early 2000s, and after a few tweaks this protocol is now in use across the species’ entire range. Thanks to the dedicated efforts of volunteers, the data collected in NH currently show a slow but steady increase in whip-poor-wills (Figure 1), which interestingly is mirrored in BBS data.

So why the fall and rise in whip-poor-will fortunes in New Hampshire? There’s a lot we still don’t know about this species, but much speculation has centered on changes to habitat. Whip-poor-wills require open areas for foraging and forested areas for nesting and tend to thrive in edge habitats or open forests such as pine barrens. Such habitats were widespread during New England’s agricultural heyday but have since grown back into forest or been lost to development. This overall loss of early successional habitat is likely behind declines in several other species such as Eastern Towhees and Brown Thrashers.

Early successional species in general are a great example of the adage “if you build it, they will come,” and are adapted to find and colonize ephemeral patches of shrubland that result from fire, logging, or other types of disturbance. This was demonstrated for whip-poor-wills as part of a NH Audubon study of habitat use in 2008-2012. In our study area, whip-poor-wills colonized a portion of forest thinned by a timber harvest within a year, and preferentially occupied other portions of the site that were adjacent to openings such as a power line right-of-way. It thus stands to reason that the recent uptick in their population could be the result of increased early successional habitat, possibly resulting from broader efforts to aid other species like American Woodcock and Ruffed Grouse. Increased timber harvest on smaller lots for economic reasons could also be a factor, although I currently haven’t investigated whether there are data to support this. Whatever the reason, it appears that whip-poor-wills have earned something of a respite, and while they’re not likely to become as common as 50 years ago, they don’t seem to be at quite as much risk as we once thought.

At the same time, the dynamics of breeding habitat are less than half the story. Whip-poor-wills migrate to Mexico and Central America for the winter, and habitat loss is an issue along their entire migratory route. New data from a tracking study suggest they also avoid areas with high light pollution on migration, which brings up another potential threat: changes to their food supply. There has been much discussion in recent years of declining insect populations (often called the “insect apocalypse”), with declines in large prey such as some moths and beetles being potentially important to nightjars such as whip-poor-wills. Light pollution, pesticides, and habitat changes could all be impacting these insects, and by association the birds that feed upon them.

If you’re one of those people who hasn’t heard a whip-poor-will for decades, the good news is that your chances are getting better. Most whip-poor-wills in NH are currently found in the Ossipee pine barrens or parts of Merrimack and Hillsborough counties. Listen for them after sunset from mid-May through early August along power line corridors, in open pine forests, or near past fires or timber harvests. Your chances are highest in the days leading up to a full moon, when calling intensity is highest. And if one is keeping you up at night, take solace in the fact that the species is possibly recovering – and that others might be a little jealous of your good fortune.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Hardwood-Mixed Forest, Shrubland

- Migration: Medium-distance

- Population trend: Declining

- Threats: Forest maturation, development, insect declines, predation

- Conservation actions: Manage for early successional or open forest habitat, minimize use of insecticides

For more information on NH Audubon’s work with the Eastern Whip-poor-will, go to https://www.nhaudubon.org/conservation/whip-poor-wills/

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available at: https://www.nhaudubon.org/conservation/the-state-of-the-birds/