(Story and photos by Pam Hunt)

If you hear an erratic “rat-a-tat-tat-tat” echoing from your roof, siding, or gutters in April or May, chances are that a male Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius) has discovered the acoustic properties of that portion of your house and is using it to announce his territory to rivals and mates alike. Like all woodpeckers, sapsuckers don’t sing, and instead drum by rapidly tapping their bills against the something that carries the sound well. Usually this is a tree, but woodpeckers will adapt to anything that resonates nicely. Sapsuckers will keep drumming into June, but then the noise tapers off as they increasingly tend to their growing nestlings. These can often be detected because they make a lot of noise inside the nest, leading to the appellation of “talking tree” in such situations. If you wait quietly nearby, an adult will eventually return with food and the begging intensifies enough to locate the nest.

In addition to being noisy, sapsuckers are famous for their distinctive foraging behavior. They drill horizontal rows of small round holes in trees and later visit them to drink the sap and eat any insects that might be attracted. They will defend these “sap wells” against other sapsuckers, as well as the hummingbirds that are also attracted to them. Sapsuckers are selective in where they drill wells, focusing on deeper xylem tissues in spring (when sap is moving upward in a tree) and on shallower phloem tissues later in the year (when nutrients are being distributed around the tree). Wells are tended for an average of three days until sap stops flowing and the woodpecker needs to make new holes, usually above the existing row. Although holes can reach high densities on some trees, there is limited evidence that sapsuckers cause long-term damage. Unlike other woodpeckers, sapsuckers don’t drill holes to extract insects from deeper in trees, instead capturing these prey directly from the bark – or sometimes by flycatching.

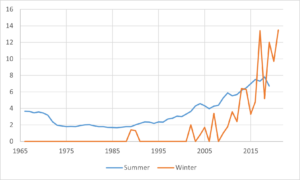

The Yellow-bellied Sapsucker is found throughout forest habitats in New Hampshire, although it is absent as a breeding species at the highest elevations and along the seacoast. It prefers forests with early-successional species such as aspen, birches, and maples, and perhaps for this reason it is more common along edges or in disturbed habitats. This habitat flexibility may also be behind its increasing population, as shown in Figure 1.

An affinity for edges probably also benefits sapsuckers during migration and winter, when most move out of the breeding range into the southeastern United States, Mexico, and the western Caribbean. Here they can be found in gardens and developed areas as long as there are a few trees to tap. Like many short-distance migrants, males tend to winter farther north than females, possibly because it allows for earlier arrival on the breeding grounds. At the same time, the sapsucker’s winter range is moving northward, probably in conjunction with climate change, and they are an increasingly common winter bird in New Hampshire (Figure 1). These sapsuckers are often at feeders, where they feed on suet and sometimes seeds. There is one intriguing case of an immature bird visiting a Concord feeder one January and an adult female in the same location the following December. The fact that it fed on the same fruiting shrub 12 months apart strongly suggests it was the same bird returning to a good wintering spot.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Forests

- Migration: Short-distance

- Population trend: Increasing

- Threats: Human-related mortality

- Conservation actions: Prevent bird collisions, keep cats indoors

More information on The State of New Hampshire’s Birds